Welcome to the NORTHERN HERITAGE Newsletter #10 and thanks you for joining our journey of discovery into the heritage of Prince George and Northern BC.

A feature of Prince George life that I noticed early on is the “cabin at the lake” — away from the city but drive-able, where urban residents withdraw for days, weekends, weeks of lakeside summer living.

There are almost two hundred lakes within 50 km of Pine Centre Mall in Prince George; big, small, accessible and remote; seasonal and permanent. Some of them have small towns nearby, access by real roads and utilities, but many are isolated at the end of rough tracks and are surrounded by forest and not much else. Options that appeal to different cabin-users.

A survey of cottage-owners at Norman Lake found that the main reasons that people invested (financially and emotionally) in cottage properties were because they offered wilderness escape that was close to home and recreational activities and because family and friends were also invested nearby. Most cabin owners visited during the short summer season with Spring lead-in and early Fall fade-out. But a small number of users have winterized their properties to be used during the long snowy months - particularly retired couples returning to the land and living lakeside year round.

The cabin at the lake is a place to opt out of life’s pressures and expectations, short or long term.

Another part of the world with a similar cottage-by-the-lake culture is Scandinavia - Sweden and Denmark - where the early 20th century rise of a large middle class with leisure led to the urge to escape the city to an idealized idyllic, pastoral landscape.

A Pastoral Landscape After a Storm by Peder Mork Monsted 1859-1941

Today 60% of Danes, for example, have access to a privately owned summerhouse.

If Danes are seeking an idyllic, romantic vision of their national past, what are PG Northerners looking for? Direct, tangible contact with the “original” northern landscape that their families and community inherited or adopted as home? Lakes as a “cottage landscape” of recreation, retreat and roughing it in the “wilderness”?

…. alternate penetration of the wilderness and return to civilization is the basic rhythm of Canadian life, and forms the basic elements of Canadian character. (W.L. Morton)

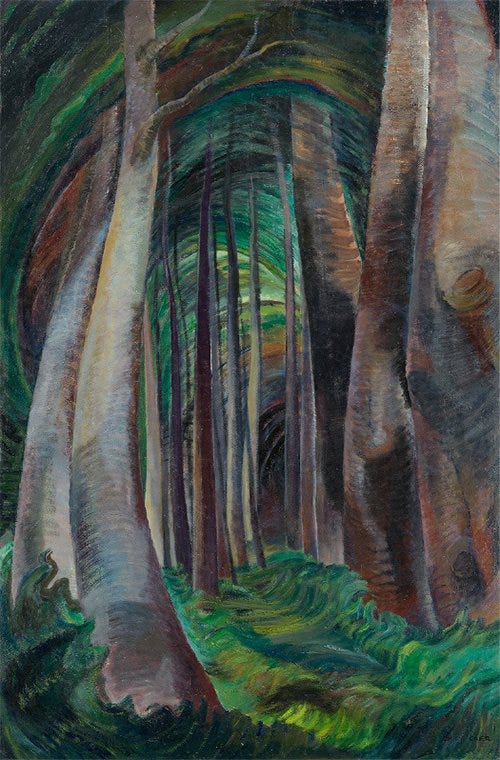

Wood Interior by Emily Carr 1932

The idea of “Wilderness” as an empty, untouched space, beautiful but dangerous, is a fundamental part of Canadian identity. Margaret Atwood states in her great book Survival, that wilderness is reflected in national art, literature and popular culture as “an alluring but potentially lethal terra nullius awaiting exploration, subjugation and purpose.”

In her essay The Wealth of Wilderness, Claire Campbell says:

Despite half a century of academic and artistic critique, our belief in the existence of pure wilderness survives quite healthily, because it has been successfully grafted into, diffused through, and constantly represented in popular culture and the language of protected places…. Affection for wilderness pervades Canadian media and popular culture; thanks to such images, a generalized boreal wilderness remains the international signifier for Canada

New Canadians must find understanding this obsession with forests, lakes and wilderness an additional challenge to adapting to their new home. My friends from Karachi or Bangkok would probably regard it all as very foreign, mystifying and maybe a bit scary. Clearly the Canadian government considers identification with wilderness and the great outdoors as a basic Canadian attribute; Parks Canada and the Department of Immigration urging “learn to camp” programs and free passes to national parks on to new arrivals.

Learn to Camp and Integrate! (Parks.canada.ca)

Free admission for Newcomers (Parks.canada.ca)

But these national and provincial parks are not wilderness; they are what Campbell calls “parcels of land designed to attract and accommodate human recreation”.

The persistent myth of “wilderness” surrounding us in Prince George and the North flies in the face of what we know about indigenous presence for millennia in the Nechako-Fraser area. Beneath the settler landscape of Prince George there are 46 recorded archaeological sites within the municipality and another 36 recorded within five km. of the city and over 2,200 recorded sites within 100 km. of city limits. These archaeological sites represent the heritage of the Carrier people who moved throughout the landscape following a seasonal round of subsistence activities, along a dense network of trails and exploiting a landscape rich in resources and generations of inherited meaning.

A cabin on a northern lake within the territory of the Lheidli T’enneh must therefore hold vastly different meaning for the members of that community — not necessarily more important or significant meaning, but undeniably older, deeper and more integrally woven into their culture and heritage. The same contact with nature, access to restorative quiet and beauty but with time depth and the certainty of generational belonging.

For all us who flee the city and burdens of daily life to share in the experience of calm, joy, ancestral links, new skills, escape or bonding — whatever our roots, we are very lucky to have access to this landscape as part of being Northerners and Canadians — whether it’s “wilderness” or not.

I just wish I had one of those cabins….

"Cottage Country" in Ontario is a bit more developed because of its longer history and proximity to the large southern Ontario cities. Though Muskoka was initially intended as an indigenous reserve, loggers and railroads pushed into the area in the mid-1800s, followed by summer resorts served by steamboats, then 2- or 3-season cabins and cottages, and now year-round mansions. There's still wilderness but it has got very expensive to live in it!