Welcome to the NORTHERN HERITAGE Newsletter # 13 and thank you for joining our journey of discovery into the heritage of Prince George and Northern BC. I am back after a short break to create an asynchronous online course for UNBC which goes live on Monday. My first experience teaching in Canada and totally online — so wish me luck!

This week I want to introduce you to the Historic Urban Landscape Approach, a planning model that can revamp our thinking and make a fundamental difference in how we treat our heritage and our city.

The Historic Urban Landscape Approach

The Historic Urban Landscape (HUL) approach is holistic and interdisciplinary. It addresses the inclusive management of heritage resources in dynamic and constantly changing environments, and is aimed at guiding change in historic cities.

HUL is based on the recognition and identification of a layering and interconnection of values – natural and cultural, tangible and intangible, international as well as local – that are present in any city. It is based also on the need to integrate the different disciplines for the analysis and planning of the urban conservation process in order not to separate it from the planning and development of the contemporary city.(Van Oers 2015)

According to the HUL approach, these values should be taken as a point of departure in the overall management and development of the city. “In this way, the HUL is both an approach and a new way of understanding our cities” (WHITRAP 2016).

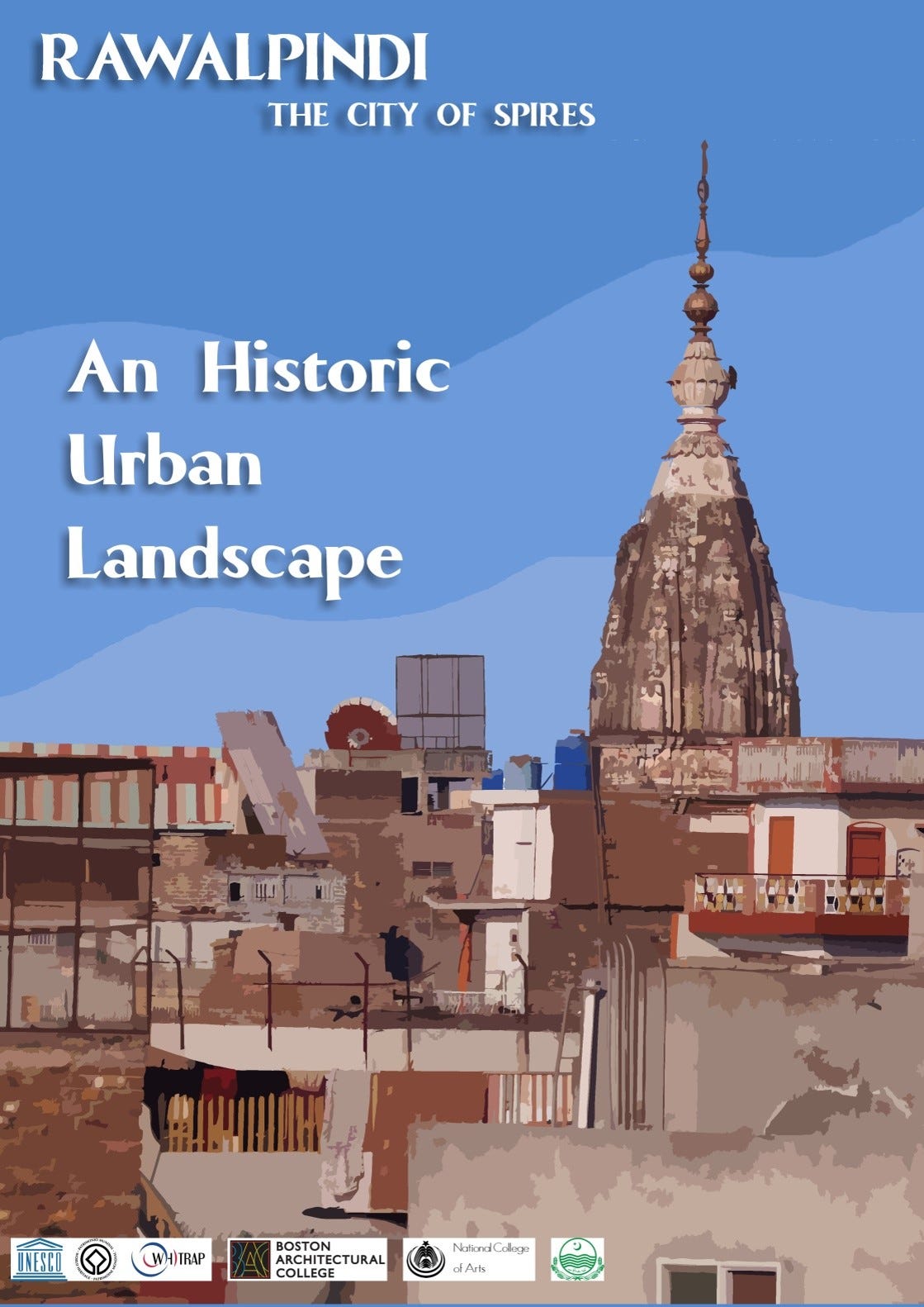

HUL was developed by UNESCO and has been piloted and applied to cities around the world. One of the important testing grounds was in Asia where I had the good fortune to carry out an HUL Pilot Project in the historic centre of Rawalpindi, Pakistan. The process of using HUL taught me some important lessons which I will return to later in this post…

First let me try to encapsulate how HUL works.

The HUL Methodology

The HUL approach recommends a set of six critical steps to facilitate implementation; these require practitioners to take into account the local context of each historic city, resulting in different approaches to management for different cities. This action plan includes:

Undertaking comprehensive surveys and mapping of the city’s natural, cultural

and human resources

Reaching a consensus using participatory planning and stakeholder consultations on what values to protect for transmission to future generations and to determine the attributes that carry these values

Assessing vulnerability of these attributes to socio-economic stresses and impacts of climate change;

Integrating urban heritage values and their vulnerability status into a wider framework of city development

Prioritizing actions for conservation and development; and

Establishing the appropriate partnerships and local management frameworks for each of the identified projects for conservation and development, as well as to develop mechanisms for the coordination of the various activities between different actors, both public and private.

In the context of these steps, the HUL approach also provides a robust and continually evolving toolkit for the management of urban heritage — “It should include a range of interdisciplinary and flexible tools, which can be organised into four different categories:

Knowledge and planning tools – to identify and protect using community mapping exercises, research and data collection

Community engagement tools - to empower a diverse cross-section of stakeholders to identify key values in their urban areas, develop visions, set goals, and agree on actions to safeguard their heritage and promote sustainable development.

Regulatory systems - could include traditional and customary systems, special ordinances, acts or decrees to manage tangible and intangible components of the urban heritage, including their social and environmental values.

Financial tools - should aim to improve urban areas while safeguarding their heritage values. They should aim to build capacity and support innovative income-generating development rooted in tradition, promoting private involvement at the local level

An informative graphic from from Li Lu 2024

Basically, HUL is what Kevin Jones calls “a series of prompts that force greater reflection on the complex social and cultural aspects of heritage and the human relationships with urban space.” (Jones and Zembal in Plan Canada 2017) The ultimate goal is to find ways that everyone - from planners, administrators and politicians to heritage workers, teachers, business owners and city residents - all can actively engage in putting heritage front and centre as we look for ways to make cities (read Prince George) the sharing and shared spaces we would like them to be.

HUL and Prince George: Can it Work?

Many of the historic cities that have adopted HUL are very big, extremely old and overflowing with ‘culture’ and ‘heritage’. Think Shanghai, Zanzibar, Rawalpindi, Naples and Aleppo. But not all - think Ballarat, Australia, Edmonton and Vancouver - smaller, newer and therefore measuring their heritage in decades/sort of a century rather than centuries and millennia. Like Prince George, these are New World cities.

My question is, “can we use the HUL approach in a small city, just over a century old, that never had great wealth, never invested in elaborate building progams and has heritage and identity much more linked to indigenous memory, its natural landscape, the everyday lives of working people and industrial heritage?”

My answer is “why not?”

The closest HUL parallel to Prince George is the city of Ballarat in southern Australia . Ballarat, with a long indigenous past, is a bit bigger than PG with a population of about 115,000 and with a slightly longer history having become a city in 1870. The big difference is that Ballarat was a gold-rush town with lots of money and they built an impressive number of mansions and ornate public buildings giving them a valuable stock of built heritage.

To be honest, I haven’t been able to find an HUL city quite like Prince George! But I still feel that official adoption of the UNESCO Historic Urban Landscape Approach would have a great deal to offer us and the city. This is what the City of Vancouver (Planning, Urban Design & Sustainability) has to say about HUL as a ‘driver of change’-

Vancouver Heritage Program adopts the HUL planning model, with its UNESCO-established principles of heritage resource management, emphasizing that a city is made up of many layers, both tangible and intangible, all which contribute to the city’s uniqueness. HUL reiterates that the safeguarding and regeneration of cultural activities and the social fabric with heritage areas and sites is as important as the protection of the physical integrity of historic places.

I like this statement because it refers to things that I tend to go on about… the layering of attributes that makes up the city, the importance of tangible and living heritage and the idea that historic buildings may be valuable but the ways we live and relate to places and each other is more so. Conserving a building is straightforward compared to conserving places and how people use and feel about them.

I like the HUL approach because it is embedded in what the community identifies as being important to them - of value - and doesn’t question what the community says. This includes making space for conflicting and contested narratives that need to be included. The other great thing about it is that it accepts, even embraces, inevitable change, asking what change is coming and how will it impact on the things we love about our city?

HUL and Lessons Learnt

I said earlier that working on an HUL Pilot Project from 2013 through 2015 in the bazaars of Rawalpindi had taught me some valuable lessons about historic cities and how we ‘conserve’ and ‘protect’ them. One of the important lessons is best described by the great Canadian heritage professional the late Herb Stovel —

Many of the historic cities we persevere to save with our modern instruments and methods arrived as objects of preservation interest after several centuries – even millennia- of evolution during which those conservation instruments were absent. What can we understand of the forces guiding changes during those past centuries that we can build into present practice?

…Cities change as a result of hundreds and thousands of decisions made inside and outside of formal and informal decision making frameworks. In essence, conservation success appears to have more to do with the ability of historic cities to manage these processes of “dynamic” change, then the effectiveness of the “static” protective instruments …normally employed within the conservation community.

It is worth asking to what extent we can identify and describe the nature of the dynamic development processes which best contribute toward realization of conservation objectives. (Stovel 2002)

Please give me your feedback

I’m frequently tempted to write about places and projects where I have worked over the years, all in Asia and far from Prince George and the North. Then I pause and wonder if maybe you, my readers, would be interested……